The Perfection of Peridot, part 6: The Zephyrs of Zabargad

Share

Despite the presence of peridot in mediaeval Europe, evidence suggests that mining operations of the island of Zabargad were still stagnant during the middle ages. The 12th-13th Century C.E. Arabic poet Ahmad al-Tifashi suggested that the peridot gemstones seen in his lifetime were acquired from the ruins of Alexandria, and for some time after the 1270 C.E. attack on Aydhab by King David of Nubia, scholarly mentions of “zabargad” gems ceased. Some sources suggest that peridot had made its way into Europe after Zabargad was visited by crusaders who ventured beyond the Sinai Peninsula and into the Red Sea; although the French crusader and Lord of Oultrejordain, Reginald of Châtillon, sailed the Red Sea in 1182, there is no evidence that Zabargad was explored by crusaders and it is much more likely that if Châtillon’s men did bring peridot back to Europe, the stones were either acquired when raiding Aydhab or obtained through typical trading practices. Following the end of the Crusades, the Sinai Peninsula became a much safer trading route, leading to a decrease in the trade activity across the Red Sea which likely contributed to the temporary disappearance of peridot in historical texts.

Egypt was eventually conquered by the Ottoman Empire in 1517, after which peridot gems began to appear in Ottoman jewellery. Most famously, the gilded walnut throne known as the “Bayram Tahti” (English: “The Gold Festival Throne”) was adorned with over 950 peridot gemstones and given to sultan Murad III in 1585. Despite the emergence of peridot jewels among Ottoman treasures, there are still no definitive descriptions of Zabargad in the Empire's scholarly texts, implying that the Ottomans were not mining period on the island and that that these gems may have come from stored wealth found in Constantinople, Alexandria, and/or Cairo, although this is not entirely clear. It is possible that academics of the time were merely unaware of Zabargad and its peridot as the Island is briefly referenced with the corrupted name “Zomorgete” in the logbook of Portuguese explorer João de Castro after he sailed through the Red Sea in 1541 under guidance of local navigators, suggesting that nearby populations knew of Zabargad even if it was not being actively mined or documented by governing powers.

After the 16th Century C.E., the history of Zabargad continued to be muddled; the next time that written information about the Island surfaced, it was still not clear how much was known about the stones found there. In 1769 the island was supposedly visited by Scottish traveller James Bruce of Kinnaird who wrote that he found green crystal fragments there known in Egypt as “siberget”, a local name for emerald, but that these stones were much too soft to have been genuine emeralds; despite an obvious similarity between Bruce’s account and the peridot of Zabargad, it is curious that the placement of the island which Bruce had provided in his writings does not perfectly match the geographic location of Zabargad. James Raymond Wellsted, a lieutenant in the Indian Navy, is said to have visited Zabargad during his time travelling the Red Sea in the early 19th Century C.E.. Wellsted wrote of the island using many names including “St. John’s Island”, “Bruce’s Island”, “Siberget”, and “Zumrud”; calling the Island by the name “St. John” has been erroneously attributed to Crusaders of the middle ages even though Wellsted is generally regarded as the source for this name, and interestingly the latter two names are both references to emerald, reflections of the continued confusion in distinguishing between the verdant beryl and peridot. In his writings Wellsted mentions the green gems found on Zabargad and describes the remnants of mining sites; he drew a connection between the stones he encountered and the green stones Pliny the Elder referred to as “smaragdus”, despite that they were actually the “topazos” stones which Pliny had attributed to the island.

It was only in 1906, after a push from the Turkish viceroy residing in Egypt, that full scale mining began again on the island of Zabargad. These operations continued until 1922 when the mining lease was acquired by the Red Sea Mining Company, who then worked the peridot mines of Zabargad for over a decade before abandoning their operations at the start of World War II. Large quantities of peridot were unearthed during this time period, and most peridot gemstones seen in Art Deco jewellery of the early 20th Century were sourced directly from Zabargad. Eventually the Island was reclaimed by the Egyptian government in 1958 under the leadership of President G. A. Nasser, but the island’s deposits had already run low and little mining activity has taken place since. In 1986, the island was given official ecological protection and has more recently become part of Egypt’s Elba National Park.

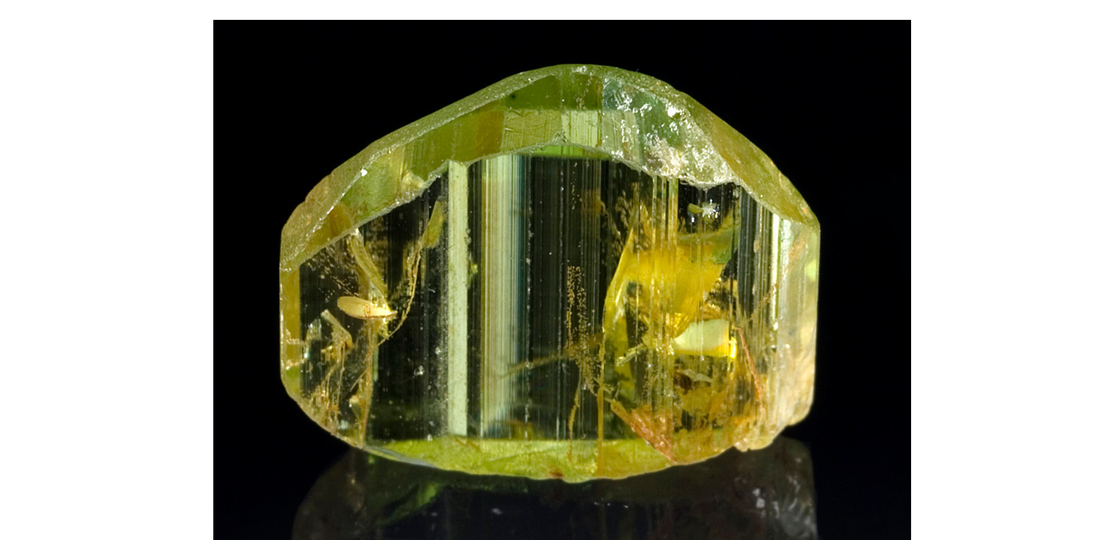

The island of Zabargad itself is now known to reside about 96.5 kilometres (60 miles) to the southwest of the Ras Banas Peninsula. A small and rather inhospitable island, the biosphere on Zabargad is limited to turtles shrubs and a few species of bird, and its shores are surrounded with some of the largest coral reefs found in any inland sea; there are no freshwater sources found on the island, a limitation that would have contributed to the logistical difficulty of mining peridot from its slopes. Part of the global rift system, Zabargad would have arisen out of volcanic activity associated with the East African Rift Valley; the magmatic activity and metamorphism which lead to the birth of Zabargad would have been an ideal precursor for the formation of the peridotites which are found in numerous places across the island. The highest point on the island, which rises about 235 metres above sea level, now known as “Peridot Hill”, the eastern slopes of which were once home to some of the largest and highest quality olivine formations found on Zabargad. About 150 mining pits have been identified on the island, with some ceramics found near them dating to about 250 B.C.E.. Most of the crystals found on Zabargad were located somewhat close to the surface and had weathered out from their host rock, making extraction of the gem materials relatively easy by contemporary standards.

With its legendary history and beautiful characteristics, peridot has certainly acquired a timeless appeal that sets it apart from many of the gemstones commonly used in bespoke jewellery pieces. A stone with class and charisma, peridot should never be overlooked or forgotten when exploring the realm of natural green gems. Peridot is truly among the classic gems of humankind and will continue to play a key part in practice of expressing creativity through jewellery and design.

© Yaĝé Enigmus