The Zing of Zircon, part 5: Fable, Formation, and Function

Share

Zircon has been treasured as a gemstone since ancient times. Evidence of zircon’s early use can be found in the Old Testament of the Judeo-Christian Bible, where the stone known as “jacinth” is listed as one of the twelve gemstones said to have been mounted in the High Priest’s Breastplate of ancient Jerusalem; in the ancient world, the names “hyacinth” and “jacinth” were used to refer to zircon gems which ranged in colour from golden orange to bright red, with the term “imperial zircon” sometimes being used today to refer to gems which fall in the middle of this range.

Zircon makes another early appearance in history as part of an ancient Hindu poem which describes the magical Kalpa Tree: a mystical tree said to have leaves made of beautiful zircon gems which was given to Earth as a gift from the Gods.

Zircon gemstones were also used in Hindu cultures in place of hessonite garnet as these two gemstones were sometimes confused for one another since they could both exhibit some of the same brown, orange, and red hues, occasionally displaying a similar lustre as well.

A “hyacinth” zircon crystal on calcite matrix from the Astore Valley in Gilgit-Baltistan, Pakistan, showing zircon’s typical pyramidal terminations; Image: Mindat/ Joseph A. Freilich

Hinduism places importance on nine celestial deities, and these deities are additionally represented by nine gemstones known as the “navratna”, literally meaning “nine gems” or “nine jewels”, which includes blue sapphire, yellow sapphire, ruby, emerald, diamond, pearl, coral, cat’s eye chrysoberyl, and hessonite garnet, with the celestial deity of Rahu (i.e. “the ascending lunar node”) being associated with hessonite garnet, known in Hindi as the “gomed” stone; it has been determined that some gomed gems of earlier eras were actually zircon gemstones which had been confused for hessonite garnet. To this day brown zircons are on rare occasions used as a substitute for hessonites in the navratna when hessonite is unavailable or no hessonites of sufficiently high quality can be found; gems used as part of the navaratna must be high enough quality called to be considered “joytish” gemstones, a term meaning “the science of light” or “the science of heavenly bodies”.

A navaratna-style ring with (beginning at the top centre and going clockwise) dark blue sapphire representing the deity Shani (i.e the Saturn), cat’s eye chrysoberyl representing the deity Ketu (i.e. the Descending Lunar Node), yellow sapphire representing the Brhaspati (i.e. Jupiter), emerald representing the deity Budha (i.e Mercury), diamond representing the deity Shukra (i.e. Venus), pear representing the deity Chandra (i.e. the Moon), coral representing the deity Mangala (i.e. Mars), hessonite garnet representing the deity Rahu (i.e. the Ascending :Lunar Node), and ruby (centre) representing the deity Surya (i.e. the Sun); Image: Wikipedia

The mineral zircon is an important part of the Earth’s crust and occurs in almost all igneous rock formations, often forming as a result of magmatic activity; due to their high melting point, zircon crystals are usually among the first minerals to precipitate from molten stone. Zircon is also frequently found in metamorphic rocks as its high heat resistance allows it to survive the metamorphosis of preexisting igneous rocks; in addition to this, zircon is common in sedimentary rocks as it frequently collects in sediments and sands due to its high specific gravity and resistance to weathering. Despite its nearly ubiquitous presence in rocks across the Earth, zircon crystals found in most rocks are typically quite small, often being less than 0.3mm in diameter; zircon crystals of suitable size for cutting into gemstones are actually rather rare in nature. The majority of non-gem-grade zircon which is actively exploited from larger deposits is used for industrial applications, with Australia and South Africa accounting for over two thirds of the world’s industrial zircon production; an exceptionally tiny fraction of non-gem-grade zircon is used in scientific research. A handful of geographic locations have produced gem-quality zircon, although the yield from these sources is usually somewhat small when compared to what is typical for many mines which produce other coloured gemstones. Some of the most important sources for zircon gems include Thailand, Cambodia, and Sri Lanka, with other notable sources including Australia, Tanzania, Nigeria, Madagascar, Vietnam, and Pakistan.

A brown zircon crystal from the Mogok Mining District in the Mandalay Region of Myanmar (a.k.a Burma); Image: Mindat/ Harald Shillhammer

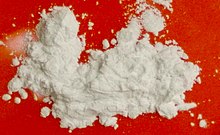

As an industrial material, zircon has a number of useful applications. Zircon is the primary ore from which zirconium metal is obtained, which is an important alloying metal in the production of surgical instruments and certain light filaments because of its resistance to corrosion. Zircon is also the primary source for the compound zirconium dioxide (ZrO2), which is used in some abrasive products, and due to its high melting point over 2,700°C (4,900°F) it is employed as a refractory material in laboratory crucibles and metallurgical furnaces. In addition to these derivative products, zircon itself is directly utilised by parts of the ceramics industry where it is used to add opacity to ceramic preparations.

Industrial zirconium dioxide (ZrO2) powder; Image: Wikipedia

© Yaĝé Enigmus