The Allure of Aquamarine, part 1 - Beautiful Blue Beryl

Share

|

Species |

Beryl var. Aquamarine |

|

Chemical Formula |

Be3Al2Si6O18 with Fe2+ |

|

Mohs Hardness |

7.5 - 8 |

|

Cleavage |

Indistinct |

|

Luster |

Vitreous |

|

Refractive Index |

1.567 - 1.590 |

|

Birefringence |

0.005 - 0.007 |

|

Dispersion |

0.014 |

|

Pleochroism |

Weak to Distinct |

|

Specific Gravity |

2.65 - 2.85 |

Among the gemstones with the longest history of human use is the wonderful gem known as “aquamarine”. This alluring stone is the blue variety of the beryllium aluminum cyclosilicate mineral, beryl, occurring in shades of sky blue, cyan, seafoam blue/green, greenish blue, and in some cases bluish green. The name for this form of beryl is derived from the latin words “aqua”, meaning “water”, and “marina” or “marinus”, meaning “of the sea”, as a direct reference to the colour of aquamarine and its resemblance to the colour of seawater. Some of the most spectacularly coloured rich blue aquamarine ever found were unearthed in Santa Maria de Itabira, Minas Gerais, Brazil, and since that time aquamarine which displays the same deep blue hue exhibited by those stones is said to show “Santa Maria blue”; other aquamarine stones which show hues that begin to approach Santa Maria blue are sometimes said to show “double blue”.

An aquamarine gem with Santa Maria blue colour; Image: Skyjems

The mineral beryl is colourless in its pure form, but aquamarine gets its characteristic blue colour from trace impurities of ferrous iron (Fe2+). Aquamarine typically occurs in variable saturation within a single deposit, often forming alongside white/colourless beryl; due to the light colouration of the stone aquamarine may appear white or silvery even when iron impurities are present. For this reason white beryl and aquamarine were typically recognized as the same mineral in the ancient world while other colours of beryl, such as emerald, were regarded as being composed of different materials. In many cases aquamarine contains trace impurities of ferric iron (Fe3+) along with ferrous iron (Fe2+), which imparts yellow colouration and gives aquamarine the green tinted blue hues that it is most known for. Aquamarine may sometimes be heat treated in order to destabilise its ferric iron (Fe3+) colour centres and give gems a pure blue colouration. While pure blue aquamarine does occur in nature, it is somewhat rare in comparison to stones with cyan, seafoam, and greenish blue colour; most commercially available aquamarine gemstones which exhibit a pure blue hue have been subjected to heat treatment.

A raw aquamarine crystal and faceted aquamarine gem from Minas Gerais, Brazil exhibiting the greenish blue hue seen in many untreated aquamarine gemstones; Image: Smithsonian Museum of Natural History

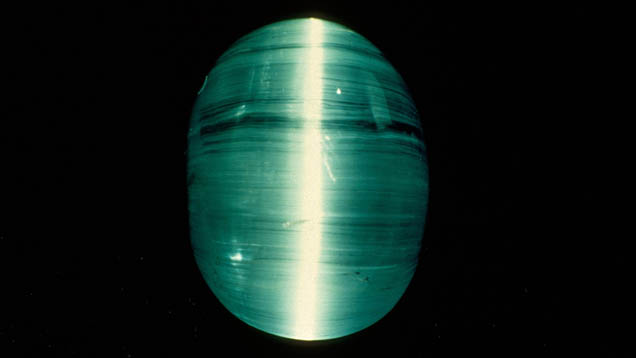

While beryl is not a common mineral in nature, aquamarine is the most common variety of beryl, but despite its abundance in relation to other colours of beryl, aquamarine is still among the more valuable beryl gemstones due to its attractive colour and widespread recognition. There are numerous localities around the globe which produce aquamarine, but the most important source of facet grade material for many decades has been Brazil, with significant occurrences being found in the regions of Minas Gerais, Bahia, and Espirito Santo. Other important sources for gem quality aquamarine include the Gilgit-Baltistan region of Pakistan, and various deposits across the island of Madagascar. Aquamarine deposits of notable size have been found in Myanmar, Vietnam, Namibia, and the USA as well. Most often occurring in pegmatites and other environments which encourage the growth of larger mineral formations, aquamarine can form crystals of the size needed to cut gemstones which are larger than what is typical for many other gem varieties. In addition to this, aquamarine crystals which exhibit very high degrees of clarity are readily available, a trait which is reflected by GIA’s inclusion of aquamarine as a gem with “type 1” clarity, the strictest classification scale used when evaluating the clarity of coloured gemstones. Although aquamarine is known for its clarity, inclusions within aquamarine crystals are not uncommon. Mineral inclusions such as pyrite, mica, garnet, tourmaline, and rutile may be found in aquamarine crystals along with others, but hollow growth tubes are a common feature in aquamarine and other beryl varieties which can help to distinguish beryl from other gemstone materials; since growth tube formation always form parallel to one another, they can produce chatoyancy within a astone when present in large enough quantities, giving aquamarine the potential to display a beautiful cat’s eye effect when such stones are properly cut.

A cat’s eye aquamarine gemstone; Image: Gemological Institute of America

In the 1970’s a deep blue beryl gemstone that challenged the finest Santa Maria aquamarine was introduced to the market, however the colour of these gems was the result of artificial radiation exposure. This particular gem is now known as “Maxixe-type” beryl, although in some cases it may be erroneously labelled as aquamarine; such stones are named after a naturally occurring beryl variety with similar chromatic character called “Maxixe” (pronounced: ‘Mah-shee-shee’) which was originally discovered in 1917 at the site of the Maxixe mine in Minas Gerais, Brazil. Naturally occurring Maxixe gets its colour from radiation exposure just like its artificially enhanced counterpart, with defects in NO3 and CO3 impurities both being considered potential chromophores; interestingly samples of natural Maxixe have also been found to contain trace impurities of cesium (Cs), zinc (Zn), lithium (Li), and boron (B) but these metals are not thought to contribute to the colour of this beryl variety. Fortunately genuine aquamarine can be easily distinguished from Maxixe/Maxixe-type beryl. Unlike aquamarine, both natural Maxixe and Maxixe-type beryl rapidly lose their colour when exposed to sunlight, with some stones fading to brown or yellowish hues. In addition to unstable colour, Maxixe/Maxixe-type beryl also exhibits different pleochroism than aquamarine; the strongest blue of aquamarine is usually seen perpendicular to the crystal’s c-axis, while the strongest blue of Maxixe/Maxixe-type beryl is usually seen when looking down the length of the crystal’s c-axis, although a small number of artificially enhanced stones have been reported to display no pleochroism at all.

A Maxixe-type beryl showing deep blue colour and exceptionally strong pleochroism; Image: Gemological Institute of America

© Yaĝé Enigmus